How we built AXL - The most creative hack of Arcesium Hackathon 2018

Arcesium recently organised a global hackathon that saw participation of ~50 teams firmwide. Hackathons at our company are always fun and many innovative projects come out of them each year. Excited to build something new, I jumped at the opportunity and teamed up with Ram Chidambaram, Shubhi Saxena and Shivaram Vasudevan.

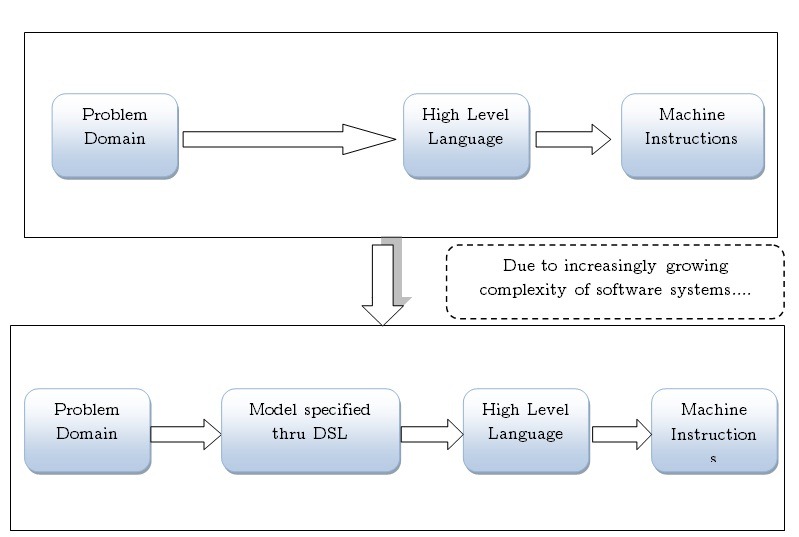

We aimed to tackle a very common challenge - developers are not domain experts and domain experts do not have the technical skills to write code describing complex logic. This challenge is faced by almost all the companies that automate/simulate complex logic for their customers in a particular domain, e.g. insurance, billing, combat solutions, etc. What is the most obvious solution? Give the domain experts the capability to read, understand (and with some skills, even write) the logic and let developers worry only about the extremely technical aspects. Enter Domain Specific Languages!

A DSL is a computer language specialized to a particular application domain. This is a contrast to general-purpose languages like C, Python and Java that are designed to let you write any type of program with any sort of logic you need.

The idea of a DSL(domain specific language) is nothing new and has been around for quite some time. However, the following are some of the ways in which we tried to make the AXL ( pronounced axle - Arcesium eXpression Language) stand out:

- Simple, English-like syntax

- Codebase size reduced by 80%

- Time taken to write a new piece of code: 2-3 hrs (reduced from several days)

- Gives users a lot more control through a UI

- Reusability - Ability to write and import operators and modules written again in AXL

Here’s how we did it:

The Design Phase

These are the minimum set of features we thought our DSL should have:

-

Should be easy to read and understand by the user (i.e. a non-technical domain expert). The keywords and semantics should basically read like English.

-

Should have built-in knowledge of domain terms and how they are computed (e.g. debit, credit, net balance, etc. for a banking software DSL)

-

Should be fairly simple to write without any programming knowledge (we tried to do away with conditionals, loops, objects, variable type, etc. as much as possible - nothing is typed and every object is a simple map).

-

Should be as succinct as possible without making it less readable (we did multiple iterations of design to ensure nothing that our language offered was unnecessary).

-

The structure and semantics of the language should follow the same progression as the real-world processes that it’s used to model. This made our language extremely intuitive for the end-users.

-

The language should be extensible. People should be able to write their own packages and libraries and reuse them in multiple places.

Based on the above design principles, we came up with pseudo-code for some of the components’ code that we are currently using in production. We then further refined this pseudo-code over multiple iterations to achieve the final sample code in AXL.

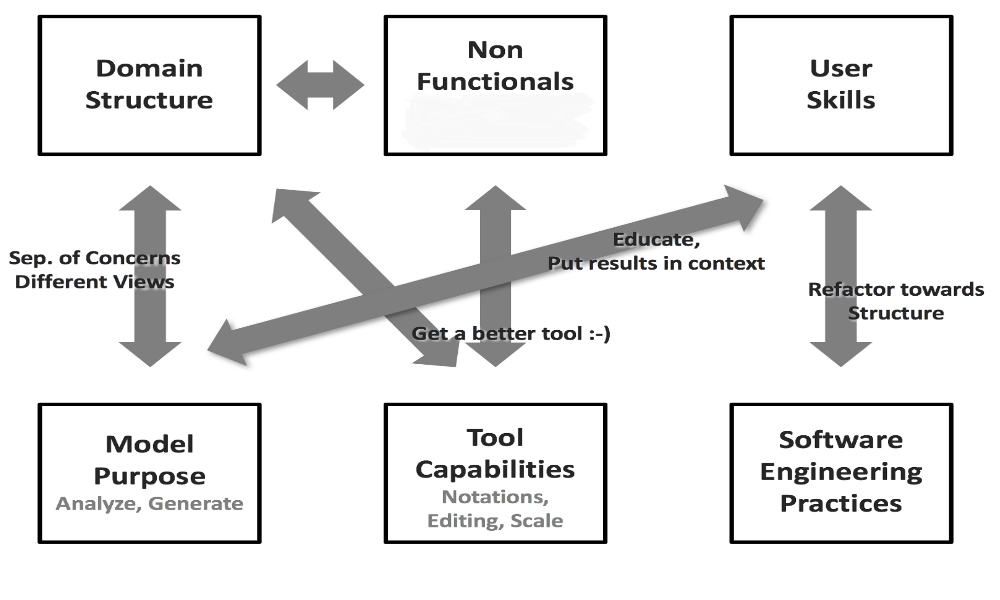

Below is a list of few guidelines that we kept in mind while writing the sample code. These could be used as general principles while desigining your DSL:

-

Try to model the various components of your processes as objects and identify the relationships between these objects. Some people use UML to do this. This will help you form a skeleton for your language. Your language should have an in-built understanding of these objects and their behaviour.

-

Never lose the context. Initially, while trying to simplify the language, we tried to avoid things like passing parameters around or having multi-level conditionals, etc. but ended up losing the current context. Your language should always have a way of telling what the current context in which the program is executing is.

-

Base your syntax upon the underlying language as much as possible (Since AXL is written in Python, we based it as much on Python as possible unless we had a very good reason to do otherwise).

-

Do multiple iterations. Read and re-read. Most importantly, make your end users read your sample code and assess if the objectives of the language are being met.

The Grammar

The grammar is essentially a set of rules that specify the syntax of the language and define what are valid/invalid usages of the language. For programming languages, we specify these rules in the form of productions. You can read more about these here:

We came up with the list of tokens, keywords and operators based on the pseudo-code and a few extensions of those in order to account for extensibility. Next, we started writing the productions for the language. We ended up with ~80 productions for the grammar specification.

The Implementation Phase

Any new language implementation requires a set of front-end and back-end operations. You can read more about these here.

Briefly, these are the modules that we built:

- Lexer,

- Parser and

- Interpreter.

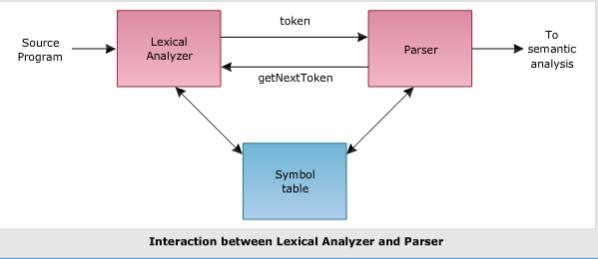

We used Python for implementing the language and picked up PLY for Lexer and Parser. PLY provides a good implementation of lexer and LALR Parser.

The Lexer and Parser

PLY provides a lot of boilerplate code that one needs to incorporate the grammar in code, read input and the lexer-parser interaction. It helped us in setting up our lexing pipeline very quickly. For parser, PLY took care of consuming the tokens from lexing phase and delegating it to the appropriate places in the parser which further enabled us to only focus on the core data-collection and syntax tree construction parts. This is where we realised some problems in our grammar productions, such as:

- Running into infinite loops

- Incorrect syntax being correctly parsed

- Precedence not getting reflected among mathematical or conditional operators, etc.

Once we quickly fixed our grammar, we were able to generate correct syntax trees for all possible cases that we could come up with. We further added certain key-value pairs that would help us efficiently consume the syntax tree in the next step.

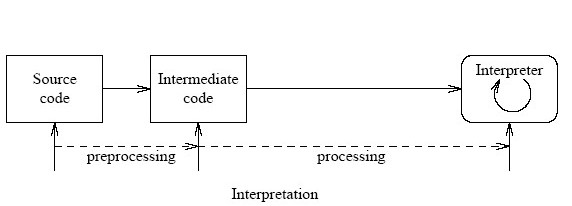

The Interpreter

Implementing a new language requires a lot of design decisions while keeping the feasibility of implementation and efficiency of complex operations in mind. We decided to not go back and forth in implementation and design phases. This helped us work on different language operators and constructs simultaneously and quickly.

Once we got the syntax tree, all that was left was to use these and interpret each statement one by one in the right context. We had created special constructs in the language that helped us determine the correct context of a statement/operation. This also helped our end-users understand “on what” they are performing an operation at any point of time.

We didn’t want to reinvent the wheel by implementing basic mathematical and conditional expressions in our language. Hence, we went on to implement the new constructs that we had introduced and let Python take care of the rest using eval() method.

Making Our Language More Accessible

Since our users come from a non-technical background, we came up with a simple UI to view, edit and run the code written in AXL. It was an extremely simplified version of an Integrated Development Environment which we called The AXL Playground.

What Next To Make Our Language Production Ready?

This essentially marked the end of our hack. While our language is complete at this point, there are certain support features that every language must have to be adopted at a large scale. Moving forward, below is the list of features we intend to develop to productionize AXL:

- Drivers to integrate the language with the existing system

- More robust error handling

- Editor support

- Version control

- Build and Deployment Mechanisms

So, this was all about AXL that we developed for Arcesium Hackathon 2018. this hack got us a 9.7 inch Ipad each for being the most creative hack of the 50+ entries!

That’s it for now. All the best for your next hack!

Update : 1st July 2019

We worked on taking AXL to production as part of Season of Code 2019 at Arcesium. You can read about it here.

Collaborator : Shubhi Saxena